|

Okay. I admit it.

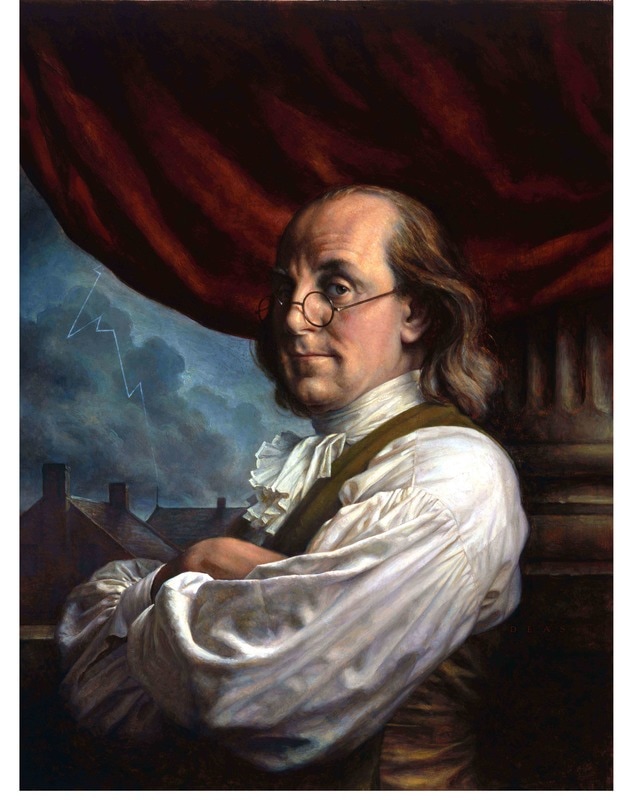

I’m a Benjamin Franklin fanboy. I can’t get enough of the guy. By 50, he was a world-famous businessman, inventor and journalist. Then he went on to set a founding vision for America, hand selecting the authors of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, and aiding both in their work. And through his writings, he proved to be a master of the aphorism—those pithy and memorable turns of phrase that instruct. A stitch in time saves nine? Franklin. God helps those who help themselves? Franklin. We must all hang together or surely we will hang separately? Franklin. It was Franklin who inspired and instructed me to write many aphorisms in Blythe, including “When there is a crisis, let your heart pray, but let your hands work.” Like much of Franklin’s work, that quote acknowledges our Creator and our need for Him, but it also sets a high bar of personal accountability for each of us: Pray, but don’t just leave it there. You’ve got to work, too, if you want to get out of any crisis. Prayer alone won’t do it. Individual action and accountability is also often required to save the day. Yes, it is vital in my view that we keep our hearts and minds open to God—to seek His guidance, wisdom and providence on all matters great and small. (And no, I’ve never prayed for a field goal for my beloved Packers even when they’re playing the Bears. Let’s not bother God with the trivial.) But we shouldn’t leave it there. We are accountable individuals. We are also capable of more than we think we can achieve, IF we act . . . if we hold ourselves to the high standard we’d expect of others in our condition. Wishful thinking never accomplished anything. It is when we seek out God’s direction and take action that we will find solutions to life’s problems. So remember: When there is a crisis, let your heart pray, but let your hands work. (Order Blythe at www.Amazon.BlytheBook.com)

0 Comments

If I have one virtue, it is honesty; if I have one fault, it is fear.

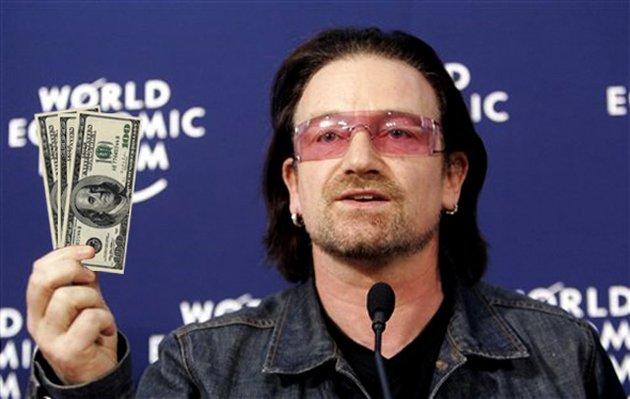

For the vast majority of my life, I lived nearly every day in fear. I lived surrounded by a thousand fears in seemingly unending variations on the theme. But I have learned to make peace with my fears because I don’t let them tell me, “I can’t.” Rather, I use them as a spur to tell me, “I must.” I grew up poor surrounded by American middle class wealth. In our home, the motto was, “First up, best dressed.” I hated never having the resources we needed to do the things I dreamed of doing. And so I challenged myself to always be working. From shoveling rocks—the worst job I ever had—to washing dishes to any other job I could get my hands on. No job was beneath me. No opportunity to learn something from each task was lost. Birth and fate started me in poverty, but I would do all I could to ensure it wouldn’t keep me there. It was how I learned the job and, at the same time, learned about human nature. Like watching Sen. Ted Kennedy and his entourage demanding the attention of a restaurant’s wait staff for the better part of a night, then stiffing us all on the tip. He was someone who was very generous with the taxpayer’s money, but, as my grandfather would say, “tight as a crab’s ass” when it came to sharing his own wealth. On the other side, there were the countless people I waited on who demonstrated such good will, patience and generosity because there was a day in their lives when they were on the other side of the counter serving customers, and they knew why it is important to treat everyone you encounter with respect. My fear of poverty didn’t drive me to envy or hate those who were rich; it drove me to do my job and then some so I could earn a place among the ranks of those who succeeded. Just because they were rich, it didn’t make me poor; inaction or giving up (or not trying in the first place) would provide me all the poverty I could image. And demanding someone take from the rich and give to me would leave me worse off because it would leave me poor in spirit. Success and wealth are not static things in America; they change. They change greatly each year. For all you hear about “the 1%,” think about this fact once written about by Thomas Sowell: In the span of our lives, well over half of Americans will find themselves at least one year in the top 1% of earners. How can that be so? Because people sell homes they’ve worked hard to own, they receive inheritances from family members who have worked hard and who have saved and looked out for their family, and in a million more variations on those themes. When you hear someone chastising “the 1%” like they are a permanent fixture in America, keep in mind that they are not “an enduring class.” Statistically, there is a good chance that you will be among them in your lifetime. I’ve been told that this attitude of hating the successful is a mindset that historically has differentiated Americans from those in other cultures; other cultures do it, Americans do not. Americans demonstrated a respect for those who rise and we have always possessed an optimism that we can rise as well. Bono once described it this way: An American passes a mansion on a hill and thinks, “Someday I’m going to own a home like that,” and an Irishman passes that same home and thinks, “Someday that bastard is going to get his.” Put me in the American camp. And that’s the great thing about living in this country in this day and age. If you have a fear, like I’ve had, you can use is as a means of inspiration to drive you to work to overcome that fear. I recognized early on that writing held a key to success. I wanted to learn how to write, and to write books and other stories. So, day by day, I read and wrote and edited and repeated those simple steps until one original story or poem or script was completed. There was nothing complicated or involved in it. It was simply about respecting each day I was given and doing something productive with it to lead me to the achievement I wanted, even if took 10,000 days to finish. I took more than a decade and a half to write and polish and publish my novel, Blythe, and during that time there were so many voices of fear in my head saying, “This is an irrational use of your time. Put it to better use.” But I kept going. Those days would pass whether I worked to my artistic ends or not. But if I did the basics each day to achieve the end I sought, I would succeed. The dream would be turned into a reality. Likewise with painting, for years I dreamed about painting something beautiful, but I never did anything tangible to get started. And then my wife surprised me with a set of paints, canvases and brushes for Christmas one year. She said, “You always wanted to learn how to paint, so paint.” It was intimidating, those first few strokes. But experience is the best antidote for fear. With each brush stroke and each completed painting, I grew more proficient and more confident. The early fear of failure faded away. What was most remarkable for me was that with each finished story and each new painting completed, a chronic fear of death I harbored since childhood dissipated. Why? Because I wasn’t really afraid of dying; I was afraid of dying before I had created something that would last and be remembered. I think that is what each of us wants: to leave some positive legacy behind that others will look on and think well of us. With each achievement, I was more firmly anchored to this world by my feet, ready to take the next step in life, whether the path took a new and unexpected turn or was on the straight and narrow. I had the experience and the confidence that comes with it and the faith in my Creator to do what my day demanded, and put that day to some better and even more productive use than the day before. Some people are anchored to this world by their feet, others by their fears. Do what you need to do today and let your fears drive you on to forget the words, “I can’t” and to remind yourself, “I must.” You will find life richer for it. (Order Blythe at www.Amazon.BlytheBook.com) I don’t understand cruelty. I never have.

On a road trip through West Virginia, I stopped in at a gas station to fill up. When I went inside to pay and get a soda, two young guys behind the counter were laughing. I smiled and gave them a nod as I passed. When I came back to the counter to pay, I noticed one of them with his hand in a glass fishbowl. He scooped out the bowl’s only inhabitant—an ordinary little goldfish. The young man held the fish up to show his buddy. His friend continued to laugh. He held the goldfish up above his mouth, his head thrown back. “Okay,” I thought, “Swallowing goldfish for sport. Are we back in a 1950s frat house?” Then the kid lowered the fish to his mouth and didn’t swallow it whole, but, rather, bit it in half. He dropped the still-living front half of the little fish back into the glass bowl, where it stared out, alive for a few more moments, but in shock. It was a petty, stupid and senseless act of cruelty against a completely innocent victim. The inhumanity of that moment never left me. Why would one being make another needlessly suffer? Those were among the most difficult passages of Blythe for me to conceive of and to write—where the innocent are preyed upon by the ruthless and wicked for sport. The antagonist of Blythe, Notté, tricks, traps and seduces the innocent to join him in his despotic world. He decides their fate. As one of Notté’s victims observes after he is attacked, “Humanity is not difficult to understand; it is inhumanity that I cannot decipher.” Men and women are created to be beings of self-determination and, as such, we are also called upon to respect the rights of others to pursue the destinies that will make them happy, so long as we do no harm to another. Incomprehensible inhumanity abounds, but so do opportunities to fight back on behalf of those in the crosshairs. Across our globe, we learn about the inhumanity one powerful person is foisting upon those who have no means to fight back. We see, in human form, the despots who are dangling the innocent above their gaping mouths, and they are ready, willing and able to inflict on the innocent an unjust punishment beyond any cruelty they have imagined. These can take the form of a vindictive mayor who limits the rights and freedoms of local citizens as a means of enriching himself and his crony pals. Or it can be a North Korean dictator who keeps his people in starvation in what amounts to a nationwide prison. It may seem like we are powerless to help those who are being preyed upon. But, if we look long enough and hard enough, we can find ways to make a difference. Through the inspiring and insightful writing of former WSJ deputy editor Melanie Kirkpatrick, my wife and I learned about the organization Liberty in North Korea. We helped fund the flight to freedom of a North Korean refugee. What a rush to think about the moment that individual tasted freedom for the first time in their life! Humanity is not difficult to understand; it is inhumanity that I can’t decipher. All the more reason we should take whatever action we can to restore to each individual her inherent human dignity, his rights and their freedoms. (Order Blythe at www.Amazon.BlytheBook.com) I have made just about every mistake a person can make, but I’ve only made them once.

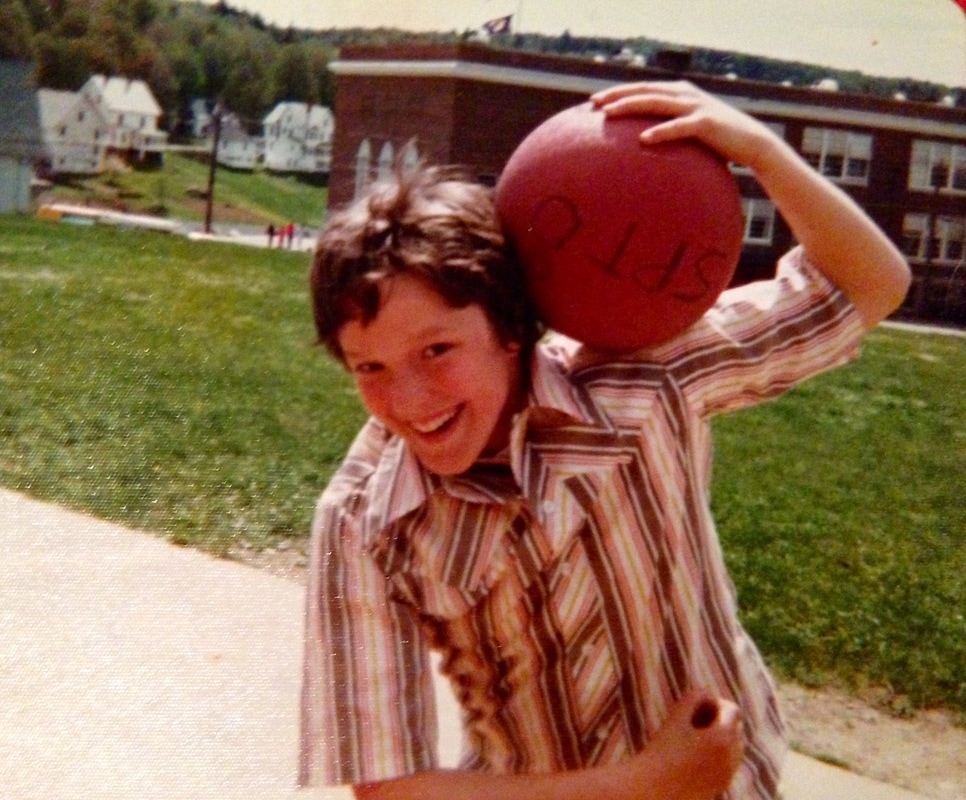

Take for instance when I received the greatest honor that could be bestowed upon a sixth grader in the idyllic little lakeside town of Sunapee, New Hampshire: I got to raise the flag at the start of the school day and, rather than doing this with a partner, which was customary, I got to raise the flag on my own. The first day, I connected the flag’s grommets to the rope’s hooks, careful not to let the flag hit the ground. I likewise attached the state flag and hoisted away. My patriotic salute accomplished, I returned to Mrs. Warren’s class. A few minutes later, our principal, Mr. Greenbaum, knocked on the door. “Mrs. Warren, who raise the flag today?” “Mr. Kramer.” “Mr. Kramer, would you come with me?” We walked together to the tall pole. As we approached it, he pointed up to the top. “When you raise the flag, you always make sure the field of stars is on top. If you hang the flag upside down, like you did, that means our country is in great trouble.” We corrected my error and re-raised the flags. The next day, I was extra careful to ensure not only that the flags didn’t touch the ground, but that the American flag was flying right side up. Then there was another knock on our classroom door. “Mr. Kramer, did you raise the flags today?” “Yes, sir.” “Please come with me.” At the base of the flag pole, he pointed out, “See how the state flag is above the American flag? No flag ever flies over the American flag.” We corrected my new error. The next day, I scrupulously ensured the flags never touched the ground, the American flag was hung right side up and above the state flag. All was right at the flagpole. As I raised the flags, a knot has somehow formed in the rope and the flags could only get about halfway up the pole. I pulled and pulled, but the rope wouldn’t budge past that point. The job finished as best as I could, I returned to class. Mr. Greenbaum knocked for a third day in a row. Well-practiced, I stood without being called upon and we walked to the pole. I learned that day about how our country mourns the death of prominent citizens. Mr. Greenbaum and Mrs. Warren wisely decided I had fulfilled my sixth-grade duties to the school and to our nation. I am pretty sure that they rightfully feared that if I were given even one more chance to get things right, somehow I would find a way to accidently burn the Stars & Stripes. As the character Haskel advises Blythe in the novel that carries her name, “There is no shame in ignorance and failing; there is only shame in not being willing to learn and repeating the same errors over again.” Perhaps someone else should run that up the flagpole and see if it flies. (Order Blythe at www.Amazon.BlytheBook.com) The first words anyone from my family can remember me saying were in a seedy little bar in Barcelona, Spain.

It was the summer of 1968. I was three years old. My father died the year before. He was 43 years young and, like JFK, he was a handsome man who would never age because of a sad fate he couldn’t foresee. My mother was left alone to raise 9 kids ranging from 15 to myself—the youngest—at two. Before that tumultuous summer would begin, the summer that would see the shocking deaths of MLK and RFK, she decided to pack all 9 kids into a VW bus—10 of us in a bus built for 9—and travel across Europe. She told me years later she had to get away from the home that still echoed with my father’s voice. (My mother wrote about that adventure and the dying and death of my father in her own book, The Road Taken: A Memoir - One VW Bus, One Widow, Nine Kids.) On one of our stops, we ducked into the aforementioned Spanish bar for a bite to eat as our culinary options were more limited back in the day. An old woman started harassing my brother, Pete, who was 13-months my senior. We couldn’t understand the words she was saying, but her hostility to him was evident. Not wanting to see anything bad happen to my best friend, I put myself between Pete and the old woman, looked up at her with all the confidence in the world, pointed my index finger up at her, and declared, “Leave my brother alone.” And, to everyone’s surprise, she did. All that was needed to stop her aggressive action against this child was someone—anyone—to stand up to her and even in a foreign tongue, to tell her to knock it off. I had a similar experience decades later, on July 4, 1987. Just weeks before, I met the love of my life—Holly, who unbeknownst to me at the time, I would marry in September of the following year. Holly, Pete, his girlfriend and I were celebrating the Fourth of July at the Esplanade in Boston, enjoying Johnny Cash, John Williams and the Boston Pops. Everyone was in a good mood, including an elderly woman in a low-profile folding chair in front of us. Out of nowhere, a grape pelted her in the back of her head. And then another. And another. The fruity projectiles were coming from behind me and were rightfully upsetting her. I casually got up and walked off to the side, then circled back to get behind whomever the grape chucker might be. Sure enough, some guy about my age, showing off for his girlfriend, was pegging the poor woman. I walked over and told him directly, “Knock it off.” He looked up, surprised someone caught him in the act and that anyone would challenge him. His first response, however, was pathetically weak: “She’s blocking our view,” he whined. I told him, “Then move.” His next response was more what I expected, albeit with more colorful vocabulary than I could have guessed: “Shut up or I’ll . . . .” Let’s just say it involved tearing off a couple of items I was pretty attached to. Anticipating a fight, the crowd around us went absolutely quiet. I looked at him square in the eyes, and with the best John Wayne slow burn I could muster said, “Stand up if you think you’re man enough to do it.” Like so many bullies, he was a coward when confronted. He didn’t move. The conflict was over. I turned to go back to my seat and was shocked to see a sea of people standing in a semi-circle around me, including my own smiling one-day-bride-to-be. We walked back to our blanket, the concert got under way, and there were no more grapes thrown at the old woman. About a decade later, I met an elderly woman named Vera Coking. Years before the casinos moved in, Vera brought a humble little boarding house next to Atlantic City’s famed Boardwalk, which was her pride and joy. Vera loved her home and living so close to the ocean. For those who don’t know, the board game Monopoly is based on Atlantic City—the closer you get to the Boardwalk, the more expensive the properties grow. Located only one block from the Boardwalk, Vera’s property was a goldmine. But Vera didn’t want to sell her land to anyone for any price. And, in this country, that was her right. Even Bob Guccione, the founder of Penthouse magazine, understood so basic a constitutional right. He offered Vera $1 million for her home, so he could construct a casino on that land, but she refused. So Guccione constructed an enormous steel cage of girders around Vera’s home as the skeleton of his construction project. Vera, her home, her property and her air rights were respected. His project ultimately fell through and the steel structure was eventually removed, but Vera and her home remained. Guccione was followed by someone who didn't respect this widow’s constitutional rights. Donald Trump convinced a government agency to take Vera’s home and hand it over to him with few restrictions on its use. He said he wanted to construct a limo parking lot where her home stood, but nothing would stop him from breaking ground the next day on a casino if he got possession of the land. I was fortunate enough to represent Vera through my work at the Institute for Justice. I directed the PR campaign that rightfully heaped mountains of media criticism at The Donald, calling into question the abuse of Vera’s constitutional rights on behalf of another private citizen for his own private gain. The one-two punch of effective courtroom advocacy by my colleague, Dana Berliner, and our media campaign ended up winning the day and saving the home Vera Coking would reside in for another decade, just as she wished. Throughout your life, you will see injustices perpetrated on the innocent, the widow, the weak, the old. We may think we don’t possess what it takes to make a difference, but, in truth, we do. We just need to stand up, take some action and make our voices heard. That is a theme that plays out time and again in my novel, Blythe. One of mankind’s greatest sins is inaction in the face of injustice. For justice to have its day, men and women of character must be its champion. (Order Blythe at www.Amazon.BlytheBook.com) |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed