|

If I have one virtue, it is honesty; if I have one fault, it is fear.

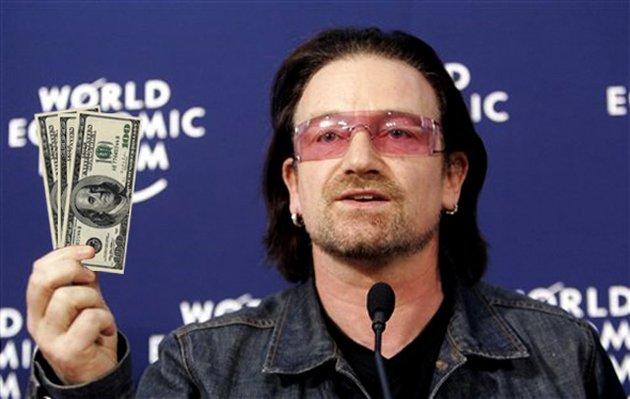

For the vast majority of my life, I lived nearly every day in fear. I lived surrounded by a thousand fears in seemingly unending variations on the theme. But I have learned to make peace with my fears because I don’t let them tell me, “I can’t.” Rather, I use them as a spur to tell me, “I must.” I grew up poor surrounded by American middle class wealth. In our home, the motto was, “First up, best dressed.” I hated never having the resources we needed to do the things I dreamed of doing. And so I challenged myself to always be working. From shoveling rocks—the worst job I ever had—to washing dishes to any other job I could get my hands on. No job was beneath me. No opportunity to learn something from each task was lost. Birth and fate started me in poverty, but I would do all I could to ensure it wouldn’t keep me there. It was how I learned the job and, at the same time, learned about human nature. Like watching Sen. Ted Kennedy and his entourage demanding the attention of a restaurant’s wait staff for the better part of a night, then stiffing us all on the tip. He was someone who was very generous with the taxpayer’s money, but, as my grandfather would say, “tight as a crab’s ass” when it came to sharing his own wealth. On the other side, there were the countless people I waited on who demonstrated such good will, patience and generosity because there was a day in their lives when they were on the other side of the counter serving customers, and they knew why it is important to treat everyone you encounter with respect. My fear of poverty didn’t drive me to envy or hate those who were rich; it drove me to do my job and then some so I could earn a place among the ranks of those who succeeded. Just because they were rich, it didn’t make me poor; inaction or giving up (or not trying in the first place) would provide me all the poverty I could image. And demanding someone take from the rich and give to me would leave me worse off because it would leave me poor in spirit. Success and wealth are not static things in America; they change. They change greatly each year. For all you hear about “the 1%,” think about this fact once written about by Thomas Sowell: In the span of our lives, well over half of Americans will find themselves at least one year in the top 1% of earners. How can that be so? Because people sell homes they’ve worked hard to own, they receive inheritances from family members who have worked hard and who have saved and looked out for their family, and in a million more variations on those themes. When you hear someone chastising “the 1%” like they are a permanent fixture in America, keep in mind that they are not “an enduring class.” Statistically, there is a good chance that you will be among them in your lifetime. I’ve been told that this attitude of hating the successful is a mindset that historically has differentiated Americans from those in other cultures; other cultures do it, Americans do not. Americans demonstrated a respect for those who rise and we have always possessed an optimism that we can rise as well. Bono once described it this way: An American passes a mansion on a hill and thinks, “Someday I’m going to own a home like that,” and an Irishman passes that same home and thinks, “Someday that bastard is going to get his.” Put me in the American camp. And that’s the great thing about living in this country in this day and age. If you have a fear, like I’ve had, you can use is as a means of inspiration to drive you to work to overcome that fear. I recognized early on that writing held a key to success. I wanted to learn how to write, and to write books and other stories. So, day by day, I read and wrote and edited and repeated those simple steps until one original story or poem or script was completed. There was nothing complicated or involved in it. It was simply about respecting each day I was given and doing something productive with it to lead me to the achievement I wanted, even if took 10,000 days to finish. I took more than a decade and a half to write and polish and publish my novel, Blythe, and during that time there were so many voices of fear in my head saying, “This is an irrational use of your time. Put it to better use.” But I kept going. Those days would pass whether I worked to my artistic ends or not. But if I did the basics each day to achieve the end I sought, I would succeed. The dream would be turned into a reality. Likewise with painting, for years I dreamed about painting something beautiful, but I never did anything tangible to get started. And then my wife surprised me with a set of paints, canvases and brushes for Christmas one year. She said, “You always wanted to learn how to paint, so paint.” It was intimidating, those first few strokes. But experience is the best antidote for fear. With each brush stroke and each completed painting, I grew more proficient and more confident. The early fear of failure faded away. What was most remarkable for me was that with each finished story and each new painting completed, a chronic fear of death I harbored since childhood dissipated. Why? Because I wasn’t really afraid of dying; I was afraid of dying before I had created something that would last and be remembered. I think that is what each of us wants: to leave some positive legacy behind that others will look on and think well of us. With each achievement, I was more firmly anchored to this world by my feet, ready to take the next step in life, whether the path took a new and unexpected turn or was on the straight and narrow. I had the experience and the confidence that comes with it and the faith in my Creator to do what my day demanded, and put that day to some better and even more productive use than the day before. Some people are anchored to this world by their feet, others by their fears. Do what you need to do today and let your fears drive you on to forget the words, “I can’t” and to remind yourself, “I must.” You will find life richer for it. (Order Blythe at www.Amazon.BlytheBook.com)

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed